Robockey was a thrilling event at the University of Pennsylvania where teams competed in hockey matches using three fully autonomous robots. Each match consisted of two one-minute sessions, during which the robots had to control an IR-emitting puck, score in the opponent’s goal, and defend their own—all while coordinating as a team.

I had the privilege of participating alongside an incredibly talented group of mechanical engineers: Jay Davey, Gaylord Swaby, and Francisco de Villalobos. My role was electrical engineering and firmware programming. Our team, Double Trouble, designed a squad of three robots: two midfielders and a goalie. What made our team unique was the midfielders’ ability to combine into a “super-robot” using magnets, while the goalie relied on a sophisticated sensor array to dominate the defensive end.

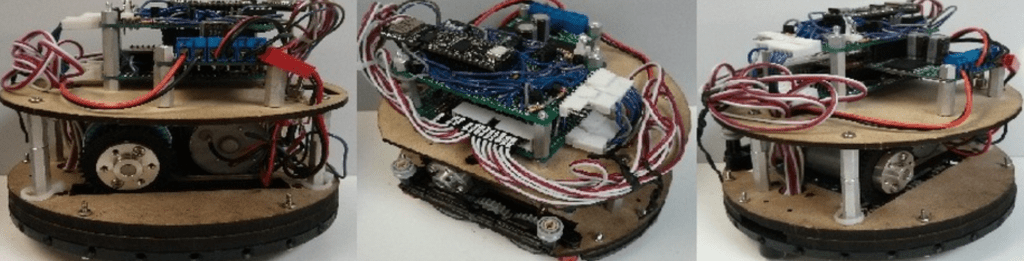

Midfielders

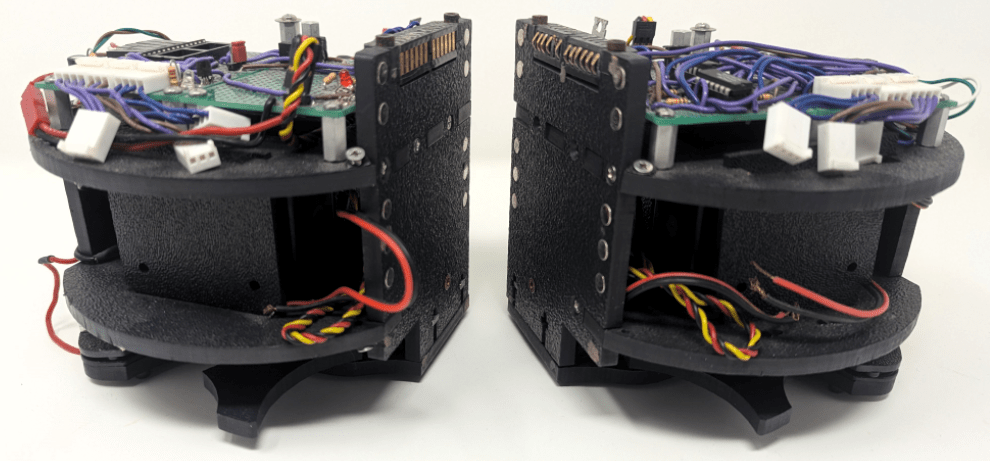

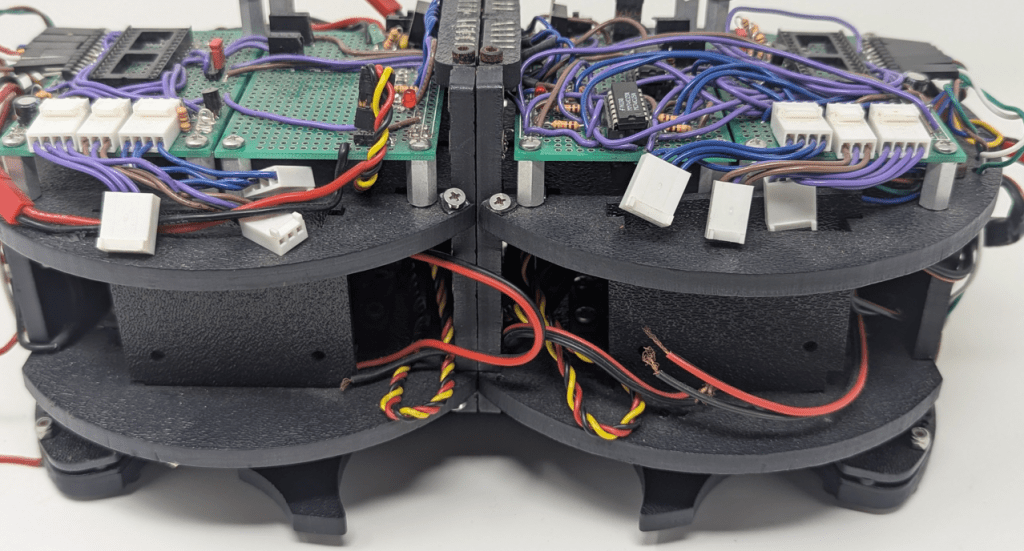

Our midfielders had a fascinating and innovative design. While each could function independently, they were also capable of joining together into a single, larger robot for increased motor power, more sensors, and better control.

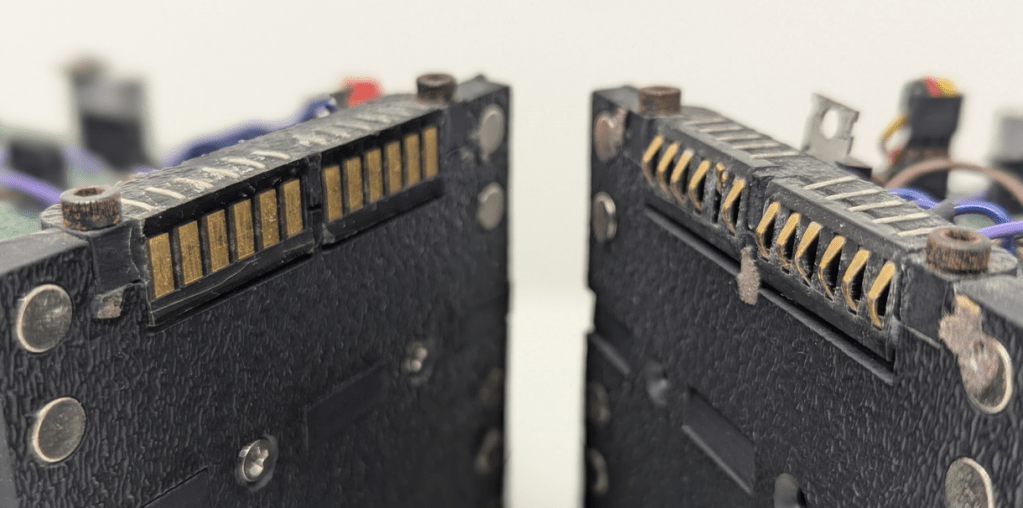

The robots connected through magnetic surfaces, carefully designed with specific polarities to snap into place when close enough. Once combined, electrical communication between the robots was established via brush blocks, allowing them to share data and act as one.

When connected, only one microcontroller (MCU) took charge, seamlessly transferring control of the “slave” robot’s motors to the “master” robot. This was accomplished using tri-state buffers as logic gates to route motor commands through the brush block interface.

Together, the joined robots were a formidable duo, able to effectively control the puck while staying within the rules for puck coverage. One of our favorite strategies was to rotate the robots around the puck, creating confusion and forcing opponent robots out of position, leaving the goal wide open for a score.

Goalie

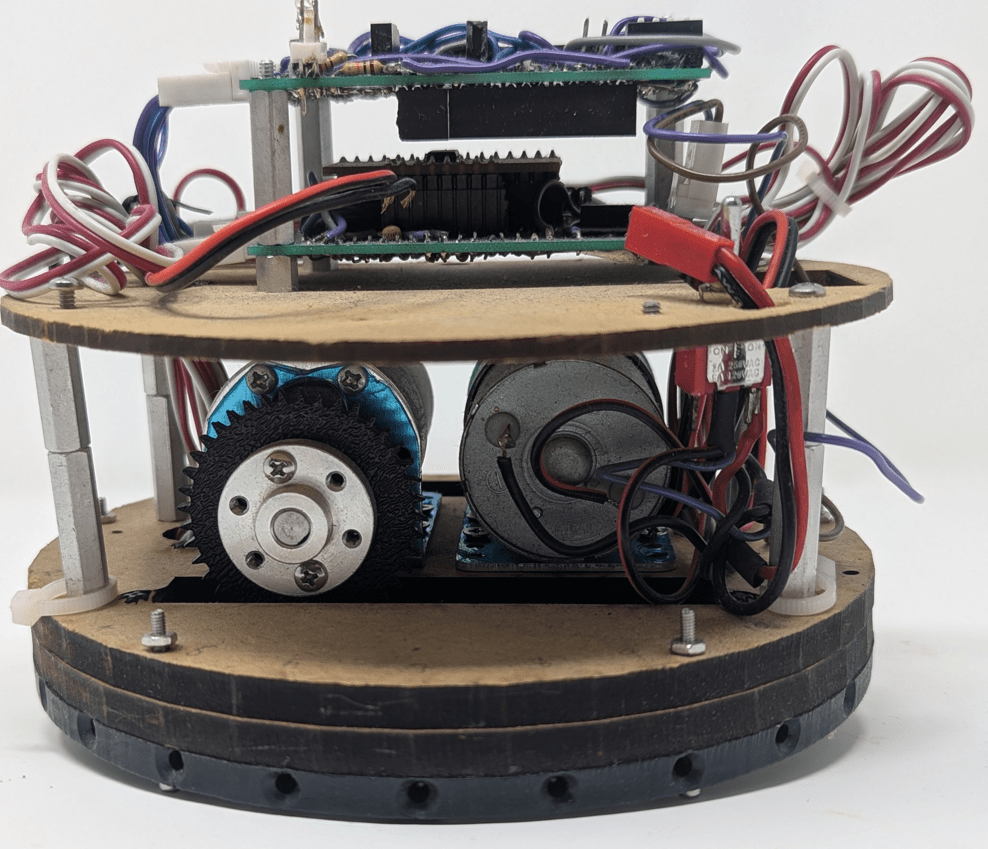

Our goalie was a beast in its own right, earning the nickname “El Loco” for its wild but effective playstyle. Designed to defend our goal with precision, it was equipped with 13 evenly spaced IR sensors to track the puck’s position.

“El Loco” featured a robust differential drive gear train that allowed it to stay agile and powerful. It could fend off offensive plays from one or even two charging robots. On occasion, it went beyond defense—snatching the puck, sliding along the rink wall, and scoring goals on its own. Watching it pull off those surprise plays was an absolute highlight of the competition.